The trouble with bitcoin: Why the crypto craze can’t last

A representation of virtual currency Bitcoin in front of a stock graph in this illustration taken Jan. 8, 2021. Dado Ruvic/Reuters

Anyone thinking of investing in the booming world of cryptocurrency may want to spend a few minutes contemplating Alex Pickard’s long odyssey from bitcoin enthusiast to bitcoin skeptic.

The Texas-born engineer began buying the digital tokens in 2013 when he was 25 years old. He recalls being inspired by the “noble” rhetoric that surrounded bitcoin in its early days. Enthusiasts boasted about the new currency’s potential to bring speedy, cheap money transfers to the world’s unbanked masses by doing an end run around banks and traditional payment systems.

Mr. Pickard loved the conceptual elegance of bitcoin’s underlying blockchain structure. It allowed cryptocurrency users to conduct secure transactions without any dominant overseer. The blockchain also insulated the system from government interference. No central bank, no policy maker, could inflate away bitcoin’s value, because the system had a built-in limit of 21 million units.

“It all fit together so perfectly,” Mr. Pickard says.

How does blockchain work?

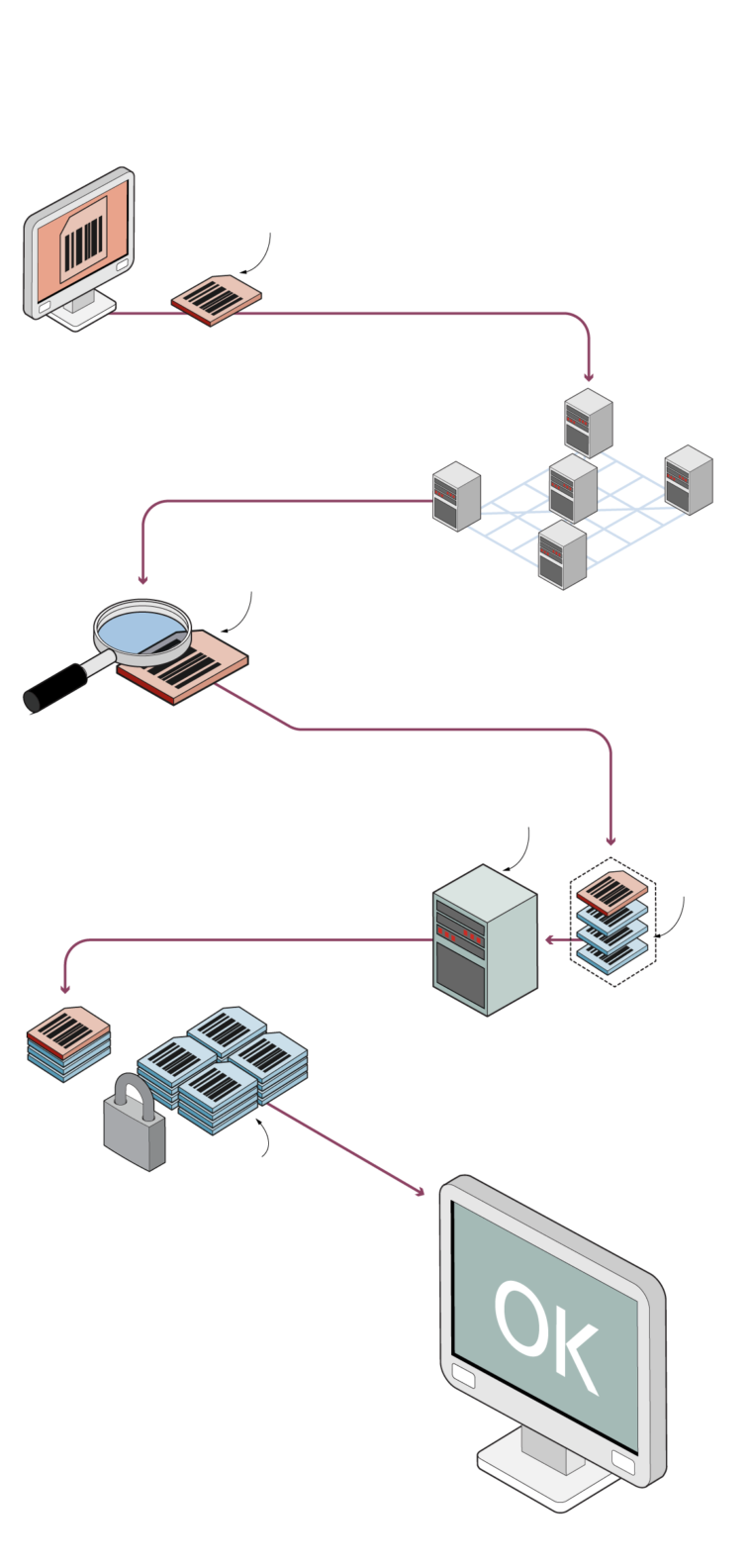

Blockchain technology allows people to transfer information and assets over the Internet without any intermediaries such as banks or brokerage firms. The following graphic illustrates how a blockchain transaction works.

A transaction is requested

(for example, a digital currency transfer)

Transaction

The request is sent to a peer-to-peer network made up of computers, which are called nodes

The network of nodes validates the transaction

Verification

The transaction is then combined with other transactions to create a new block of data that is stored in a digital ledger using cryptography

New

data

block

Digital

ledger

The new block is added to the existing blockchain. Each block references the block before it, creating a permanent and unalterable record

Secure

ledger

The transaction is complete

IAN McGUGAN, Alexandra Posadzki and

john sopinski / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: pricewaterhousecoopers

How does blockchain work?

Bitcoin runs on what is called a blockchain – a type of public ledger, distributed across many computers. These computers work together to verify transactions on the ledger and prevent fraud. They produce a chain of time-stamped transactions that cannot be altered (at least, not without a nearly inconceivable amount of effort). Each new transaction becomes part of a new block on the chain.

A transaction is requested (for example,

a digital currency transfer)

Transaction

The request is sent to a peer-to-peer network made up of computers, which are called nodes

The network of nodes validates the transaction

Verification

The transaction is then combined with other transactions to create a new block of data that is stored in a digital ledger using cryptography

New

data

block

Digital

ledger

The new block is added to the existing blockchain. Each block references the block before it, creating a permanent and unalterable record

Secure

ledger

The transaction is complete

IAN McGUGAN, Alexandra Posadzki and

john sopinski / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: pricewaterhousecoopers

How does blockchain work?

Bitcoin runs on what is called a blockchain – a type of public ledger, distributed across many computers. These computers work together to verify transactions on the ledger and prevent fraud. They produce a chain of time-stamped transactions that cannot be altered (at least, not without a nearly inconceivable amount of effort). Each new transaction becomes part of a new block on the chain.

Transaction

A transaction is requested (for example, a digital currency transfer)

Verification

The request is sent to a peer-to-peer network made up of computers, which are called nodes

The network of nodes validates the transaction

Digital

ledger

New

data

block

The transaction is then combined with other transactions to create a new block of data that is stored in a digital ledger using cryptography

Secure ledger

The new block is added to the existing blockchain. Each block references the block before it, creating a permanent and unalterable record

IAN McGUGAN, Alexandra Posadzki and

john sopinski / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE: pricewaterhousecoopers

The transaction is complete

CI Financial aims for first Ethereum ETF as bitcoin exchange-traded funds find hungry market

Bitcoin emergence as ‘digital gold’ could lift price to $146,000, says JP Morgan

Want to bet on bitcoin? Here’s a Canadian fund to consider

In mid-2017, flush with windfall profits on his early purchases, he decided to become a full-time bitcoin miner. He quit his job in quantitative finance and became possibly the only person to ever move from sunny, glamorous Newport Beach, Calif., to far less sunny, far less glamorous Wenatchee, Wash.

Mr. Pickard’s new home was in a community of 35,000 people located beside a giant hydroelectric dam on the Columbia River. Thanks to that dam, Wenatchee boasts one undeniable attraction – some of the cheapest electricity in the United States.

Low power prices were vital to Mr. Pickard’s plans because bitcoin miners earn units of the cryptocurrency by operating arrays of specialized computers that race against rival miners to solve computational challenges. Electricity is a miner’s second-biggest expense, after the computers themselves.

Mr. Pickard soon had banks of computers up and running. Fuelled by cheap power, they began to earn several thousands of dollars a day mining bitcoin.

Then came a knock. “It was 20 guys from the power utility, at my door, in the dead of winter,” he recalls. They told him he had to unplug his mining operation because it was straining the local power grid. Mr. Pickard thought he had carefully studied and obeyed all the local regulations; the utility had a different view and wasn’t inclined to be patient.

He scrambled to find a solution. He shipped his computers to a site in Chicago, but it was early 2018 and bitcoin prices were tumbling. His machines were losing value by the day.

Should he continue to pursue his bitcoin dream? He was discouraged by the increasing dominance of big players. “I was competing against much bigger, better-funded miners,” Mr. Pickard says.

He was also beginning to question the broader case for bitcoin. Enthusiasts for the cryptocurrency had spent years touting its potential to replace cash. That vision no longer made sense: Processing fees had risen to roughly US$10 a transaction, a bite big enough to discourage anyone from using bitcoin for small, everyday purchases.

Meanwhile, it was becoming obvious that bitcoin could not easily scale up in size from a hobby project to a true currency. Technical limitations in the original design put a limit on how many transactions the bitcoin system could process per minute. A stream of newer payment systems – PayPal, Apple Cash, Cash App – were offering superior alternatives for instantaneous cash transfers, especially within the United States.

The bitcoin community responded to these developments with a new sales pitch: Bitcoin was now supposed to be “digital gold,” an asset that wasn’t tied to any utilitarian function, but one that could act as a hedge against inflation.

This new positioning makes little sense to Mr. Pickard. Now back in sunny Newport Beach, as vice-president of research for Research Affiliates LLC, a quantitative investing firm, he wrote an analysis in January that takes issue with the revamped rhetoric around bitcoin.

Among other things, the report points out that bitcoin’s wild price swings in recent years – an 83-per-cent plunge in 2018, followed by a sevenfold increase over the next two years – displayed absolutely no relationship to the market’s underlying inflation expectations, which barely budged during that time. If people are supposed to be buying bitcoin as an inflation hedge – as digital gold, in other words – this lack of correlation makes no sense.

Even more unsettling are suspicions that bitcoin’s price has been manipulated through purchases using another cryptocurrency, Tether, which purports to be backed one-for-one by the U.S. dollar. John Griffin of the University of Texas and Amin Shams of Ohio State University documented the evidence for this possible manipulation in a 2019 academic paper titled Is Bitcoin Really Un-Tethered?

In February, Tether and cryptocurrency trading platform Bitfinex agreed to pay a US$18.5-million penalty to settle a New York State probe into their conduct. The two groups admitted to no wrongdoing but agreed to stop operating in the state. “Bitfinex and Tether recklessly and unlawfully covered up massive financial losses to keep their scheme going and protect their bottom lines,” Letitia James, New York’s attorney-general, said in a scathing statement.

To Mr. Pickard, who no longer owns bitcoin, the settlement underlines some of the reasons to be wary about what the crypto movement has become. Fans no longer tout bitcoin’s ability to create a better, fairer financial system. They seem more interested in making a profit. True enthusiasts celebrate their willingness to “hodl” – a deliberate misspelling of “hold” that has become a synonym for buying and sitting on digital tokens, hoping they will go up in value.

Gusts of sentiment can drive gains in the sector over the short haul, Mr. Pickard acknowledges. But anyone who is thinking of investing should realize that purchasing bitcoin amounts to gambling on an asset that may be manipulated in price, doesn’t produce any cash flow and no longer has much practical value as a means of money transfer.

“People are falling over themselves to get into the game because there is money to be made,” he says. “Crypto is now seen as an investment, something that will go up in value. But very few people are actually using bitcoin as it was originally intended.”

Words of caution about bitcoin may seem quaint after a year in which its price has shot from less than US$10,000 to more than US$56,000, and financial institutions have rushed to embrace cryptocurrencies.

Mastercard, PayPal and Bank of New York Mellon have all announced initiatives to make it easier for customers to store crypto and transact in the new tokens. In February, Toronto-based Purpose Investments launched the first exchange-traded fund to track bitcoin. Also last month, CI Global Asset Management of Toronto filed a preliminary prospectus for an ETF that will invest in ether, another cryptocurrency.

Enthusiasts tout such moves as proof that crypto is the wave of the future. That seems more than a little giddy, though – at least, in the simple “buy bitcoin” sense.

A more realistic view is that the recent initiatives show the financial sector is doing what the financial sector always does: It is acting as a middleman for customers who want to buy and sell various assets, while raking in a steady stream of fees along the way.

Does this amount to a monetary revolution? Not really. Recall that bitcoin was originally intended to undermine other payment systems. It is only as its technical limitations have become clearer that those same systems have begun to dabble in it. “Mastercard and PayPal are getting into bitcoin precisely because bitcoin is no longer a threat to them,” Mr. Pickard says.

Other expert observers are just as dismissive. In a February speech, Bank of Canada deputy governor Timothy Lane declared that bitcoin and its crypto cousins “do not have a plausible claim to become the money of the future.” Cryptocurrencies’ verification methods are too costly and their value too unstable to function as everyday cash, according to Mr. Lane. To him, the recent run-up in their prices looks like a “speculative mania.”

Nouriel Roubini, a fire-breathing professor of economics at New York University, tore into bitcoin and other cryptos in a recent Financial Times opinion piece. He pointed out that none of these new forms of money actually act as a unit of account – “virtually nothing is priced in them.” Neither are they stable stores of value: Bitcoin’s history is one of enormous run-ups in value followed by spectacular crashes.

Anyone hoping crypto will emerge as a viable alternative to the existing financial system has to confront the constraints of its architecture. Bitcoin allows five transactions per second while the Visa network can handle 24,000, according to Prof. Roubini’s calculations.

“Risky, volatile bitcoin doesn’t belong in the portfolios of serious institutional investors,” he writes. “Many of its retail backers are suckers being manipulated by an army of self-serving insiders and snake oil salesmen.”

Ray Dalio, the billionaire founder of giant hedge fund operator Bridgewater Associates, offers a slightly more complimentary take on bitcoin and its ilk, but with a similarly downbeat conclusion.

In a January report, Mr. Dalio lauded bitcoin as “one hell of an invention.” He said it will likely be around for a long time and will possess some value. But he noted that any similarity between real gold and digital gold is limited.

Bridgewater Associates Chairman Ray Dalio attends the China Development Forum in Beijing, China March 23, 2019.

Thomas Peter/Reuters

Unlike gold bullion, the supply of digital currencies is essentially unlimited. New tokens will continue to come along, increasing the potential supply of crypto alternatives. Anyone buying bitcoin for its scarcity value may want to think again.

Meanwhile, it is a sure bet that governments are not going to passively stand by and watch if cryptocurrencies begin to supplant their own fiat currencies. Exactly how crypto regulation will evolve is unclear. Also murky is how investors will choose to store their wealth or how secure bitcoin holdings are from cybertampering.

“That is why to me bitcoin looks like a long-duration option on a highly uncertain future that I could put an amount of money in that I wouldn’t mind losing about 80 per cent of,” Mr. Dalio concludes. Faint praise, indeed.

So, given all these excellent reasons to be cautious, why is there is so much excitement around crypto? The simplest explanation is that bitcoin is riding the same gusts of enthusiasm that have carried the U.S. stock market to record heights in recent weeks.

A pandemic-inspired shift to online commerce, remote work and streaming services has helped lift tech stocks, in particular, to extreme valuations. Cheap money, government stimulus cheques and legions of locked-down, bored retail investors have helped to amplify this prevailing exuberance.

At a time when a barely profitable maker of electric vehicles like Tesla Inc. can shoot up tenfold in value since January, 2019, it is not entirely surprising that a digital token like bitcoin can shoot up twelvefold over the same time span. (Or that Tesla founder Elon Musk can decide to invest US$1.5-billion in the crypto and accept it as payment.)

If bitcoin’s rise is simply a manifestation of the exuberance around all things techy, then it is likely to fade as the global economy emerges from its pandemic stupor.

Rising interest rates will likely increase the attractiveness of rival investments, such as bonds, and draw money away from assets like bitcoin that offer no yield. Meanwhile, a mass return to the office could end the boredom that has pushed many retail investors into speculative bets on companies such as GameStop Corp. and Tesla.

However, anyone betting on a quick return to prebitcoin normality may want to think again. Whatever happens to bitcoin’s price over the next year, it has one undeniable success to its credit – it has demonstrated that blockchains and computer networks are capable of challenging traditional notions of money. The changes it has helped set into motion are likely to ripple through markets in the years ahead as even newer forms of electronic cash come into play.

The most prominent manifestation of this trend is likely to be a profusion of central bank digital currencies (CBDC) – a type of money that will resemble bitcoin in its ability to be used easily online, but that will be backed by a central bank instead of an impersonal algorithm.

In the same speech in which he described bitcoin as a speculative mania, Mr. Lane of the Bank of Canada promised the central bank “will continue to explore the possibility of a digital currency that would be an electronic version of the banknotes that Canadians trust and rely on.”

Like the Bank of Canada, central banks everywhere are wrestling with how to respond to the declining usage of paper money and the simultaneous rise of private payment systems as well as non-sovereign, alternative digital currencies. Bitcoin was the first major tech-based challenger to the cozy world of government-backed money, but more ambitious projects are gaining momentum.

A 3D-printed Facebook Libra cryptocurrency logo is seen in front of displayed German flag in this illustration taken, September 13, 2019. REUTERS/Dado Ruvic

DADO RUVIC/Reuters

Consider Diem. It is the new name for the Libra digital currency plan proposed by Facebook executives back in 2019. In its original form, the project envisioned an online currency that would be backed by a basket of fiat currencies. Regulators gave it a cold shoulder because of concerns it could enable money laundering.

The Diem Association has listened to the criticisms, relabelled itself, and attempted to answer the regulatory issues. Based in Zurich, it now spans 26 members, including Canada’s Shopify Inc. The association aims to start offering “stablecoins” – digital tokens on a secure blockchain that will be tied to specific fiat currencies or to a basket of them. Its first token, linked to the U.S. dollar, is widely expected to roll out this year, or as soon as the project can win approval to operate as a payments system from the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority.

The prospect of such private tokens sends a shudder through many central bankers. As Mr. Lane noted in his speech, widespread use of privately issued stablecoins could potentially result in the issuing organization having access to enormous amounts of data on every aspect of the economy.

“A technology company could become the gatekeeper of the entire economy, with concerning implications for privacy, competition and inclusion,” he warned.

No wonder then that central banks would prefer to make their own digital currencies the preferred method of exchange. Exactly how this would all work is still as clear as mud. The Bank of Canada, for instance, is mulling schemes from three teams of university researchers, but has yet to commit to doing anything. However, it seems a near certainty that the next few years will see a profusion of new forms of digital money and money-like tokens competing for consumers’ attention, both in Canada and around the world.

The implications for bitcoin itself are unclear, but lean negative. Stablecoins from the likes of Diem and CBDC, the central banks’ alternative, are likely to offer all the online convenience once promised by bitcoin, but without annoying drawbacks, such as high transaction fees or abrupt price swings.

Mr. Pickard, the bitcoin veteran, says anything is possible. If enough people become enamoured of bitcoin for whatever reason, it could climb higher for a while. But he sees much more reason for caution than optimism.

One reason is the natural speculative cycle. As bitcoin’s price rises, people who got in at much lower levels feel a natural temptation to start cashing out, creating a powerful downdraft. On at least three occasions since its launch in 2009, bitcoin has lost 80 per cent or more of its value.

“The general rule is pretty clear,” he says. “Whenever people get excited to talk about bitcoin, and prices run up, there will be a crash.”

What is money?

The frenzy around bitcoin reflects our shifting notion of what constitutes money.

In centuries past, money took the form of physical objects such as cows, gold, sea shells or paper bills. Today, physical money seems nearly quaint. Coins and paper bills are fading from use in Canada and elsewhere. Money is now largely nonmaterial, whether it is in the form of bank deposits, central bank reserves or credit card transactions.

“Money today is a type of IOU, but one that is special because everyone in the economy trusts that it will be accepted by other people in exchange for goods and services,” according to a Bank of England paper in 2014.

So do bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies qualify as reliable IOUs? Depends whom you ask.

Crypto enthusiasts argue bitcoin can, in theory anyway, fill the three traditional roles of money – it can act as a unit of account, a medium of exchange and a store of value.

Skeptics scoff at those claims. Nouriel Roubini, the New York University economist, points out that crypto is not really a unit of account (few goods and services are priced in bitcoins). Neither is it a good medium of exchange (because of bitcoin’s limited ability to process large volumes of transaction). Nor is it a great store of value, given its propensity to jump up and down in price.

One of the big differences between bitcoin and fiat currencies is that bitcoin is anchored by an algorithm while fiat money is overseen by a central bank. Bitcoin has no central authority – it depends on an elaborate cryptographic protocol to protect its integrity – while fiat money’s value hinges on the actions of the humans at the central bank.

To bitcoin fans, the impersonal nature of bitcoin (including hard limits on how many tokens the system can create) makes it inherently more trustworthy than its fiat counterparts.

Jeff Booth, a Canadian businessman and author of The Price of Tomorrow: Why Deflation is the Key to an Abundant Future, argues that central banks have a built-in bias in favour of inflation. He sees bitcoin as a better store of value than government-created currencies.

“I think it’s highly likely that bitcoin becomes the reserve currency,” he says, with fiat currencies pegged to the cryptocurrency rather than the other way around.

Others find that prospect unlikely, precisely because it doesn’t take the political dimension into account. Ray Dalio, the billionaire founder of hedge fund giant Bridgewater, notes that governments want control over money and credit within their borders. They are not likely to cede that authority easily.

“I suspect that bitcoin’s biggest risk is being successful, because if it’s successful, the government will try to kill it,” he wrote in a recent note.

Be smart with your money. Get the latest investing insights delivered right to your inbox three times a week, with the Globe Investor newsletter. Sign up today.

Published at Sat, 13 Mar 2021 15:00:00 +0000

Comments

Loading…