Cemetery a historic landmark in shopping center – Centennial Citizen

At the Pioneer Hills shopping center just off Parker Road, visitors can find the typical features of a suburban retail destination: a Bed Bath & Beyond, a PetSmart, a handful of chain restaurants.

But right between the Chick-fil-A and another retail building — near the middle of the parking lot — there’s a cemetery.

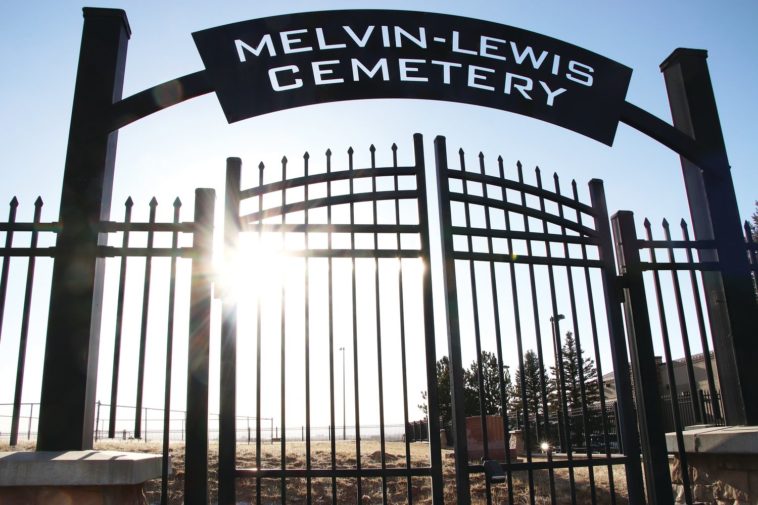

It’s called the Melvin-Lewis Cemetery, a former part of a small community called Melvin that once sat near the Cherry Creek watercourse.

John and Emma Lewis, who once owned a farm in the area, purchased the land that included the cemetery in 1883, according to the Cherry Creek Valley Historical Society.

“Most residents were forced to move when the Cherry Creek Dam was built,” the society’s website says. “This burial ground fell into disuse and was abandoned.”

Decades later, suburban sprawl crept right up to the cemetery, which ended up preserved as part of the shopping center. It’s not known for sure who was buried there — or even how many people once were, according to the historical society.

“We have more questions than answers,” said Garry O’Hara, the society’s president.

Although the cemetery, which previously sat amid an open field, was a “prime candidate to be bulldozed over 20 or 30 years ago,” O’Hara said, it now holds a historical landmark designation from the City of Aurora, the city in which the shopping center is located.

Here’s a look at what’s known about the cemetery, which sits just outside of Centennial near Chambers Road.

Historic resting place

Arriving in 1859, the Melvin family’s settlement in the area “proved invaluable to fellow westward travelers” and eventually grew into the Melvin community, according to historical information from the City of Aurora.

Travelers were buried at the cemetery, likely beginning with the Melvins’ arrival, according to the city. The Lewis family purchased the cemetery from the Melvin family.

John and Jane Melvin had built a ranch in the area in the 1860s, according to the historical society. The Melvin place soon became known as 12 Mile House, a station along Cherry Creek.

The “mile houses” sat every two to three miles along the Cherokee/Smoky Hill wagon trails from Kansas, named based on their distance to the intersection of Colfax Avenue and North Broadway in Denver, according to Arapahoe County’s website. Out of the original six mile houses, only 17 Mile House and Four Mile House exist in their entirety today, the website says. The buildings also included Seven Mile House, Nine Mile House and 20 Mile House, according to the National Register of Historic Places.

At mile houses, travelers could get a meal, spend the night, rest their animals and have minor repairs made to coaches or wagons, according to the county’s website.

In addition to travelers, the remains of individuals who donated their bodies to medical research were also buried at the cemetery from 1957 to 1986, according to Aurora’s website.

In 1957, the property that included the cemetery was acquired by the University of Colorado, and it was used for research from that point, O’Hara said.

“Over time, the cemetery became abandoned and vandalized,” O’Hara said. Among the only remains left are cremated remains of around 1,600 people who donated their bodies to science after death, now interred in a chain-link fence enclosure in the middle of the cemetery, O’Hara said.

`Valiant’ fight

Before the shopping center arrived, “nothing at all” sat near the cemetery, O’Hara said.

“The only thing that was there is the caretaker’s house for the University of Colorado and a few sticks in the ground where graves were supposed to be,” O’Hara said.

The shopping center’s development didn’t happen without a fight — O’Hara and others felt the development would be “an eyesore” and produce too much noise, O’Hara said.

Clarice Crowle, one of the founders of the historical society, helped lead a letter-writing campaign to the local governing body at the time — likely the Aurora City Council, O’Hara recalled.

“She had our friends in the newspaper offices write stories about that and put the Melvin-Lewis Cemetery in headlines so that people would notice it,” O’Hara said. “And it was a losing cause, but it was very valiantly done by members of our group and others.”

O’Hara isn’t sure whether the developer planned to preserve the cemetery at first, he said. But ultimately, the developer agreed to build a wall around the cemetery, along with a “beautiful gate,” O’Hara said.

“So we’re happy about that — they did what they promised,” O’Hara said.

The cemetery and much of the surrounding shopping center land are owned by a company called Collett, a real estate firm whose corporate office sits in North Carolina, according to county property records.

The company purchased the shopping center from “Site Centers/DDR, who purchased it from the Greenberg group,” said Erik Christopher, managing principal with SRS Real Estate Partners. Collett is a client of SRS, Christopher said. Greenberg was the original developer, he added.

“The preservation (of the cemetery) was part of the land-use protections that accompanied the shopping center acquisition,” said Bobbi Conigliaro, asset manager for Collett. “Although we do not have a right to change it, we are happy to do our part to protect it.”

Conigliaro did not have other information to offer about the cemetery’s history, she said.

O’Hara guesses the original developer bought the land from the University of Colorado or that it became city land after about 1983, but he couldn’t say for sure. He didn’t know whether the university bought the land from the Lewis family.

The shopping center’s buildings were constructed in 2002, according to county records.

‘Place of honor’

O’Hara’s historical society isn’t sure when the first and last burials of remains that weren’t research-related took place at the cemetery.

“All we know is the first burial was possibly as early as 1860s, and the last was (likely) 1910,” O’Hara said.

At least some remains were exhumed and moved to Fairmount Cemetery in east Denver, O’Hara said.

The historical society doesn’t know for sure who was buried there, but it’s more certain about one person: Emmaretta Hawkey Lewis, likely interred there in the 1890s, according to the society.

“She died in the 1890s, possibly in childbirth,” O’Hara said. She was married to one of the Lewis men, he added.

“We don’t know who’s there still, we don’t know where if they were, we don’t know when they were placed there and when they (may have been) exhumed,” O’Hara said. “I try to find out myself, but I run into brick walls.”

The structures that now lie in the cemetery are “bases,” on top of which would have gone the memorials of the buried. Generally, no full tombstones stand now, O’Hara said.

A small memorial in honor of those who donated their bodies to science has sat in the cemetery, and another memorial was made by the Cherry Creek Grange in 1961 in honor of the travelers buried there, O’Hara said. The grange was an organization that included farmers who traded ideas about agriculture, he added.

The cemetery was in bad shape before the shopping center development and the changes it brought, O’Hara said.

“It’s much better,” O’Hara said. “It’s still not in the greatest shape, but it’s at least in a place of honor where it belongs.”

Published at Tue, 26 Jan 2021 04:03:00 +0000

Comments

Loading…